Q-and-A with Hannah Barrueta Sacksteder, WomenStrong’s Program & Equity Manager and Lead for Language Justice

In the United States, where 20 percent of people speak a language other than English at home, language justice is often associated with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Legal and healthcare settings dominate the conversation about ensuring that people who don’t speak English are able to understand their rights and medical treatment.

But what is language justice for an international organization headquartered in an English-speaking country? How did WomenStrong observe the need for it and start to offer interpretation for speakers of other languages? We spoke with our lead for language justice, Hannah Barrueta Sacksteder, about this —and about her goals for the future of translation and interpretation services at WomenStrong. Read our interview with her below.

How did you start thinking about the need to bridge language and communication gaps at WomenStrong?

I grew up in Mexico with an American mother. In Mexico, many indigenous languages were squashed —even though now the government has tried to revive some of these. I always thought this was a terrible injustice.

When I moved to France for one year to immerse myself in the language, I struggled with being able to communicate. This raised my consciousness about the frustration or lack of opportunity that language barriers can create.

I learned about a growing group of activists who are dedicated to addressing power imbalances in their language-access work and connecting it to a vision for social justice and inclusion.

Language justice helps to foster shared power, promote inclusion, and dismantle traditional systems of oppression that have disenfranchised non-English speakers.

How did you become aware of the concept, language justice?

Language justice helps to foster shared power, promote inclusion, and dismantle traditional systems of oppression that have disenfranchised non-English speakers.

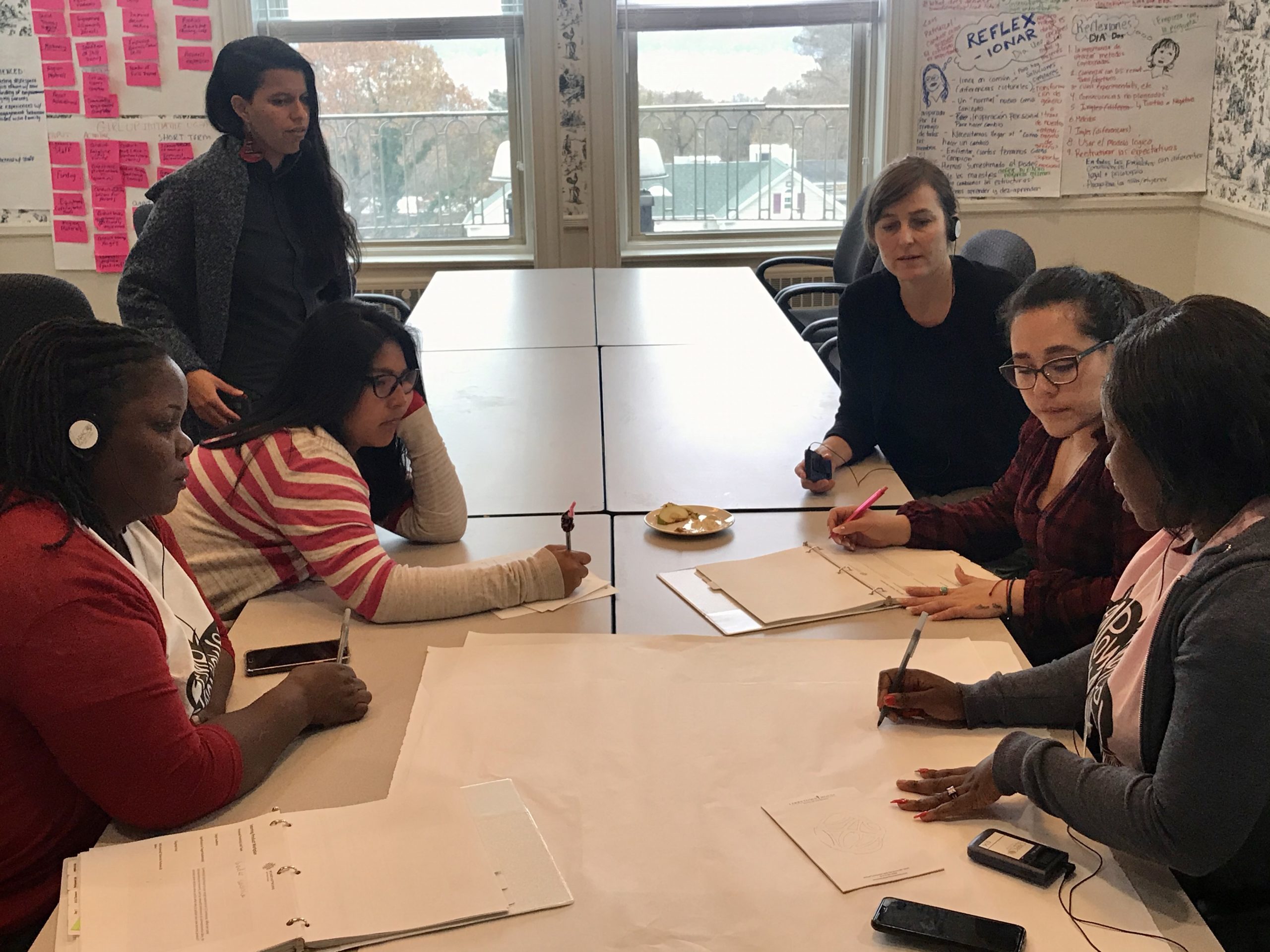

I started thinking about the concept during our first WomenStrong retreat, which was in person in 2019. Two speakers asked for live interpretation. The interpreters introduced the topic at the beginning of the meeting.

After the pandemic hit, we wanted our partners’ staff to join online events and meetings for the Learning Lab, and many of their staff didn’t speak English. Little by little as we arranged for interpreters, the composition of the groups on the calls changed, and the nature of our conversations changed. We were able to get more word-on-the-street information about what interventions were working, and how we might need to adjust some things.

Partners were grateful to have the opportunity for all their staff to participate in meetings with WomenStrong.

Why did you draft a language-justice policy for WomenStrong?

We felt like we wouldn’t be true to our mission if we didn’t have language justice. Without it, we wouldn’t be showing we value our partners’ context and cultures.

We wanted our partners and their staff to feel comfortable enough to speak up, to share their experience. Sometimes people are uncomfortable with their accents, and we want people to feel safe. As a group, we need to accommodate. We wanted our partners’ staff to bring their authentic selves to meetings — to listen, learn, and understand. Language justice was a way to live up to our principles.

How does WomenStrong implement language justice?

The need for live interpretation exploded at the beginning of the pandemic, but we found some organizations that typically work with refugees and contracted with a few for six months.

Whenever we plan a call, we proactively ask partners whether or not they need interpretation.

I brief the interpreters ahead of the video call. I set up the Zoom and make sure the presentations are translated into Spanish and French. My goal is to ensure that partners and their staff can fully participate in every phase of the activity.

We recognize that providing language justice is a process — one of creating spaces, fostering equity, and accepting that it will be a learning experience. We’re always open to hearing ideas from our partners.

What do we do if one of our alternative languages — Spanish and French — aren’t the native tongue of one of our partners?

If two or more partners express a need for interpretation into another language, we seek to make that happen. We do this, for instance, with sign language. In English, we can offer closed captioning.

What other translations do you provide to ensure language justice?

We make sure to translate emails, presentations, key documents, and other activities into our official languages. We also have to be sensitive to people from different regions. We ask interpreters to be flexible and incorporate partners’ Spanish or French dialects when possible.

How did partners and their staffs respond to WomenStrong’s new language-justice policy?

Feedback was very positive. People were concerned about the number of languages worldwide —hundreds. We spoke with our partners and came up with Spanish and French. We made sure they’d receive translations.

Partners appreciate that we’ve created a more equitable space, where more than just the English-speaking senior executives could be involved. We have seen that the calls are more diverse, and the opportunities to speak with more members of partners’ teams change the Learning Lab dynamics.

What has WomenStrong’s experience been, since you offered translation?

Implementing our language-justice policy was a real aha moment for us. We noticed how much richer conversations were after we offered interpretation.

Lots of our partners have thanked us for our new policy. They say they feel appreciated and heard, now that they can all participate in the space of the Learning Lab. We are doing everything to decolonize development. It’s a continuous process that we are happy to change depending on need.

What would you advise to be the best way to ensure language justice?

I’d advise listening. WomenStrong has a language justice policy because we listened to our grantee partners and realized that the way we did things could be improved. It is important to us that our work and activities respond to the needs of the partners, starting with the very basic principle of understanding each other.

If you’d like to implement language justice at your organization, find people on your team who are open to the idea of creating more equitable spaces, and be OK with not having a perfect program. Language justice is a process of learning and changing. Accept that at least in the short-term, you won’t achieve a flawlessly equitable language space. However, this does not mean you can’t work toward one. Do what you can!